Teamwork: science fiction vs. science fact

In the January 2017 issue of Communications of the ACM there is a terrific article by Thomas Haigh, an author, historian, and professor.

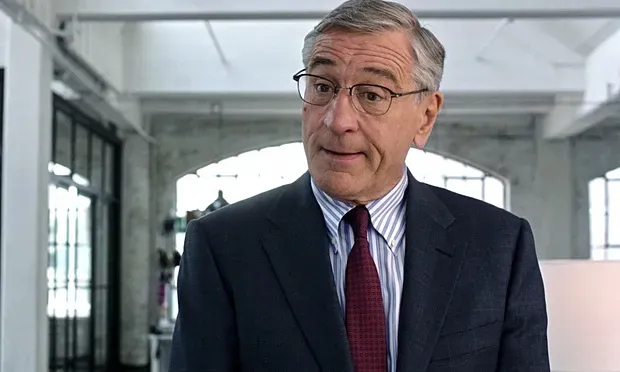

In the article, Haigh examines the depiction of Bletchley Park and its staff in contemporary media. He pays special attention to Alan Turing and his portrayal by Benedict Cumberbatch in the recent, Oscar-winning movie The Imitation Game. In fact, he calls it like he sees it from the start: “the film is a bad guide to reality but a useful summary of everything that the popular imagination gets wrong about Bletchley Park.”

Details of the work done at Bletchley were kept secret until the mid-1970s when they were declassified. Since then, many books have been written (quite a few by Bletchley alumni), and both documentary and Hollywood movies made. Some of these movies have been more fiction than fact, unfortunately, and this relates to one of Haigh’s points: the contemporary portrayal of the code breaking efforts at Bletchley is often as sensational as it is misguided. I think that, given the staggering human accomplishment associated with Bletchley, that is a disservice; the retelling of the story doesn’t need to be embellished to be both engaging and inspiring.

One of the first dramatizations of Alan Turing’s life and work was in the 1996 movie Breaking the Code (watchable online!). Derek Jacobi plays Turing as a brilliant but socially naïve man, rather innocent in his view of the world. Until recently, Breaking the Code was the only movie I had to help form my understanding of Turing, as a man and a scientist. The movie was based on Andrew Hodges’ definitive biography of Turing, Alan Turing: The Enigma.

Interestingly enough, The Imitation Game was also based on Hodges’ book. This provided me a second interpretation of Turing and his work within contemporary cinema. Jason Shankel, a writer, filmmaker, and coder, has posted a solid article comparing the two movies with respect to their depiction of Turing, relative to Hodges’ biography, and I recommend reading it.

[A third movie is sometimes mistaken as being about Alan Turing, if only peripherally — Enigma. This movie, released in 2001 and based on Robert Harris’ book of the same name, takes place at Bletchley Park during the war. Code breaking is central to the plot but Alan Turing is not portrayed; this is an entertaining movie, but the plot and characters are fiction.]

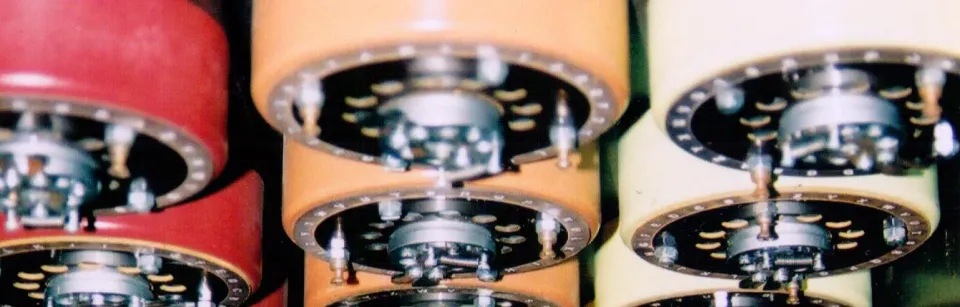

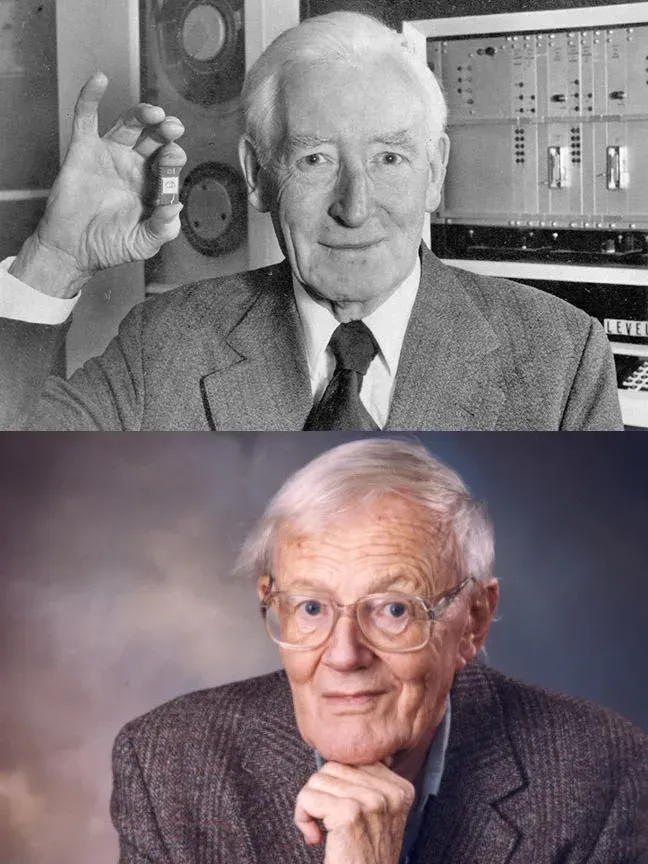

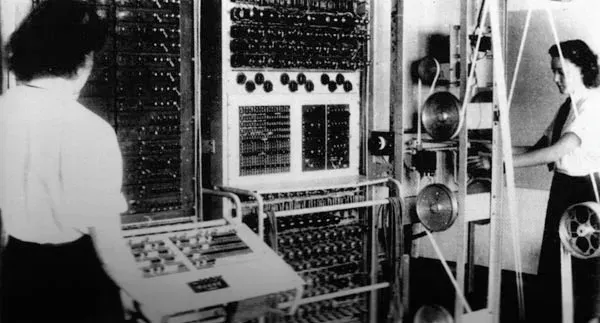

While Haigh does a thorough job of illustrating the differences between The Imitation Game and historical fact (and the implications thereof), he should be acknowledged for highlighting other individuals and groups that contributed to the work at Bletchley. Without disparaging Turing, Haigh discusses Bill Tutte (who progressed the work on the Lorenz cipher dramatically and spent his later years in Waterloo Region) and Tommy Flowers (who designed Colossus, arguably the first electronic programmable computer; Haigh — and even Flowers himself — prefer to call it a processor, lacking the hardware for arithmetic and not being programmable). He also praises the work of not only the mathematicians, but of the engineers who helped design and build the Bombes and Colossus (“perhaps nobody would pay to see a movie centered on heroic production engineers, brilliant Bombe operators, and inspirational government procurement specialialists” — nonsense, I would! But I also wanted The Bletchley Circle to be exclusively about actual decrypts and the impact they might have had on the war effort).

Of the approximately 10,000 people working at Bletchley to break codes, 75% were women. While cryptographers were almost exclusively upper middle class men (there were a few exceptions), women were Bombe and Colossus operators, running the machines to decrypt messages, filing room staff to manage the massive repository of punched cards, and ‘wrens’, members of the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS). Their contribution was invaluable and, thankfully, more recent attention is being paid to that aspect of Bletchley.

I think it is important to give credit where credit is due. I believe we are better when we work on diverse teams comprised of generally nice, smart humans. I’ve spent time thinking (and writing) about whether prototypical ‘rock star’ contributors are more trouble than they’re worth (don’t get me wrong, Alan Turing was awesome). For all these reasons, I love Thomas Heigh’s article.

When the majority of people will learn of Bletchley Park and its history from a single movie (likely The Imitation Game), we need to expect more. As an audience, we should demand more than the same old formula, trotted out to dilute a piece of history, an independently and fiercely engaging story that deserves better. As Heigh says:

More generally, we need to consider the impact our stories have on future generations. We need to appreciate that each piece of media our children consume shapes their understanding of the world (“German ciphers single-handedly broken by Alan Turing” vs. “10,000 people worked together to crack the code”; isn’t the latter even more compelling as a story?!).

The work we’re doing as a society obviously isn’t irrelevant (nor is it even boring) just because we do it as a team — on the contrary. It worked for Bletchley, no matter what the movies tell you.