Rock star developers are dead. Right?

I am a child of the 80’s. I was raised on a nutritious breakfast of arcade games, post-Reagan Saturday morning cartoons, The A-Team, heavy metal (on cassette), Dungeons & Dragons, and iron on t-shirts — the good stuff.

This was before the (non-academic) Internet was available: writing a report for school meant going to the library and reading the encyclopedia (and hoping no one else had the A-D volume you needed), the sound of a modem handshake was music to one’s ears, and when one of the only ways to get software was to type it in by hand, read from the back of a Compute!’s Gazette.

I remember spending hours reading MLX code to my dad as he carefully typed the hex values into the Commodore 64 (thank goodness for checksums!). What a way to be introduced to the work involved in writing software, to the magical world of controlling hardware, and to being able to create alternate realities. Of course anyone who had a Commodore 64 computer knows that it was used mostly for games. And, boy, there were some great ones.

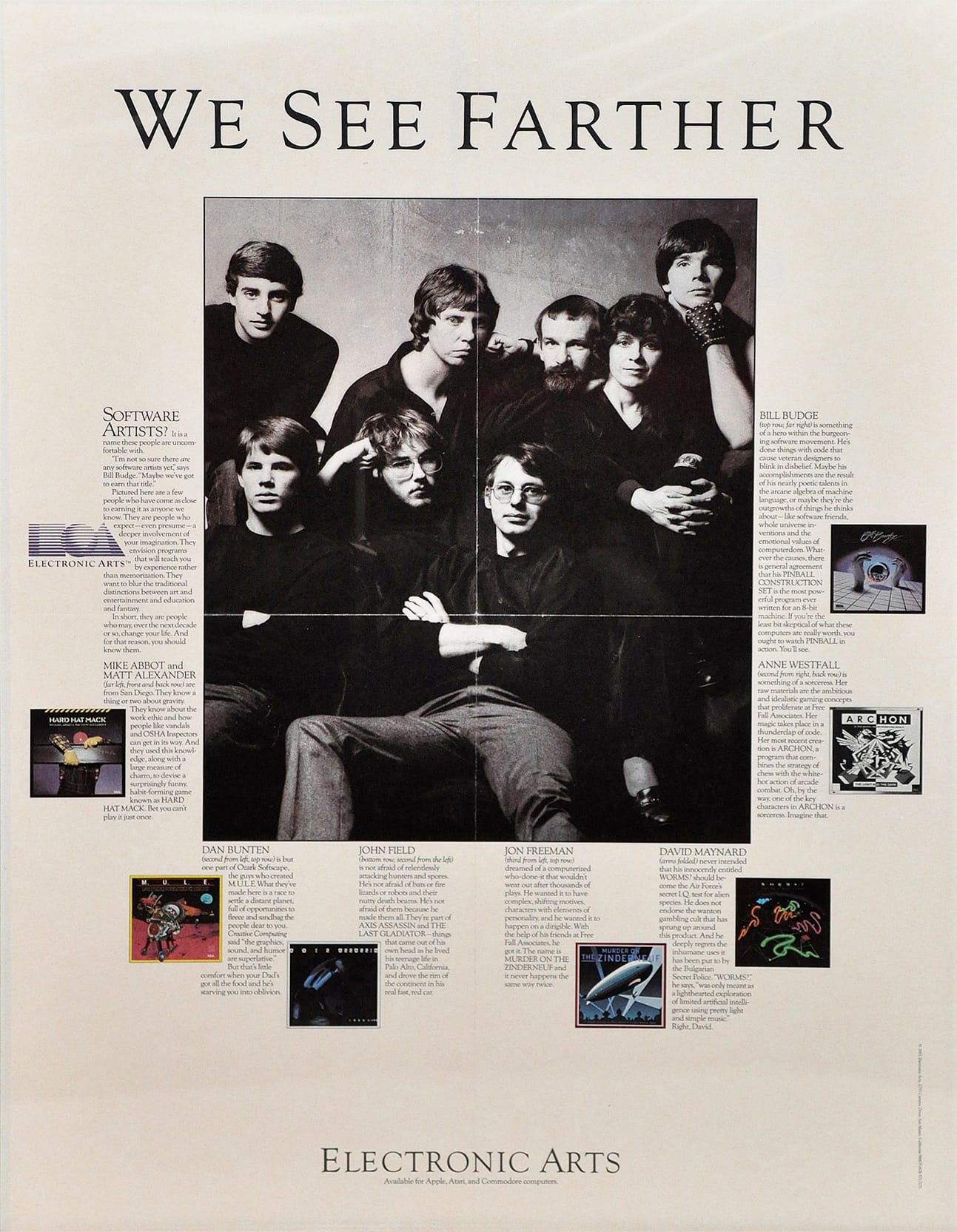

We See Farther

In those exciting days of early consumer computers, games were currency — both literally and figuratively. They bolstered the value of your platform. They demonstrated the hardware most aggressively. And they were swapped like trading cards on the playgrounds (admittedly in a 5¼" square form factor).

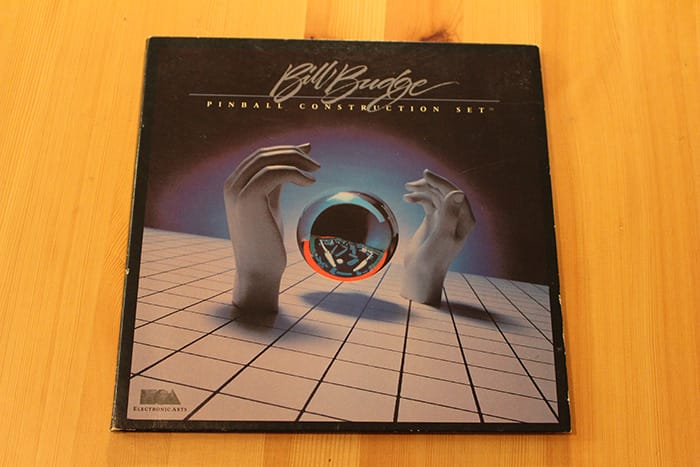

Electronic Arts (EA) was perhaps the heaviest hitter when it came to game publishing companies for the Commodore 64 (and for other platforms too). They seemed to have a consistency about the games; that logo — the cube, sphere, and pyramid — were an assurance of quality.

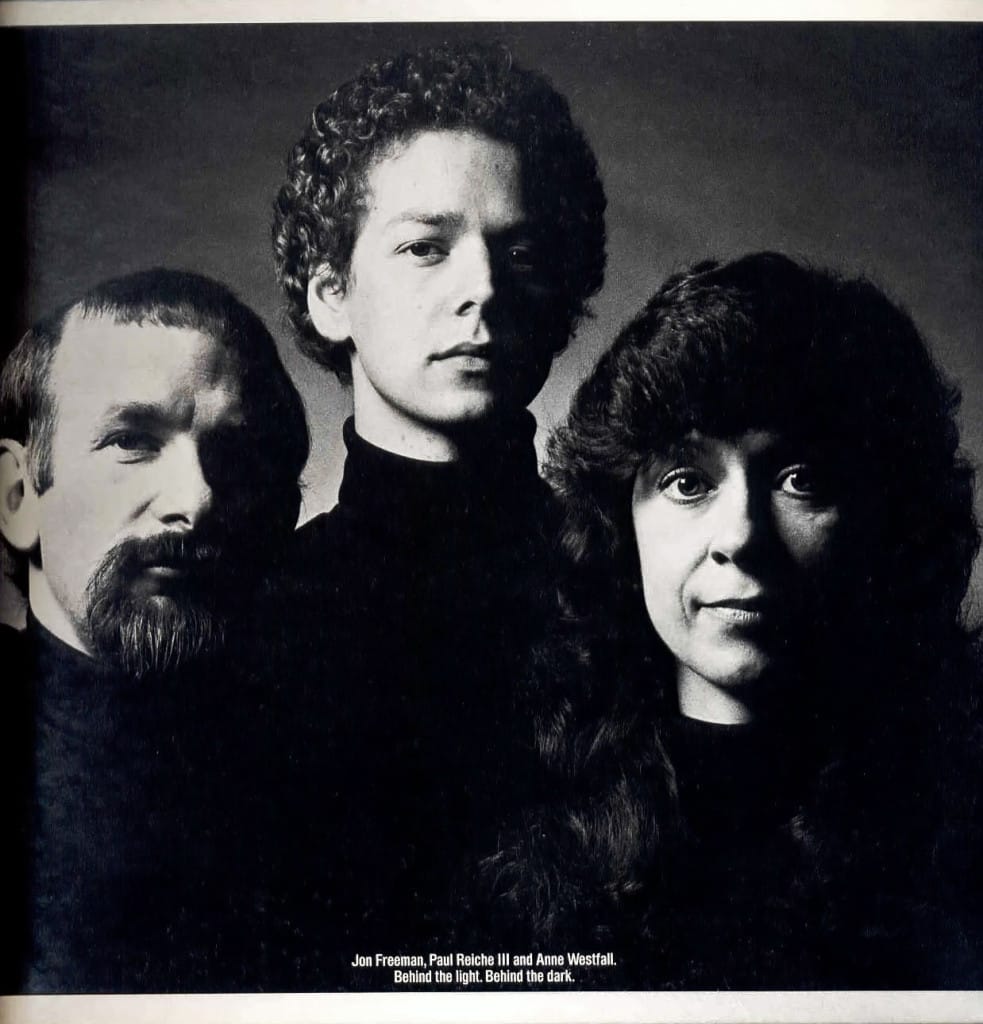

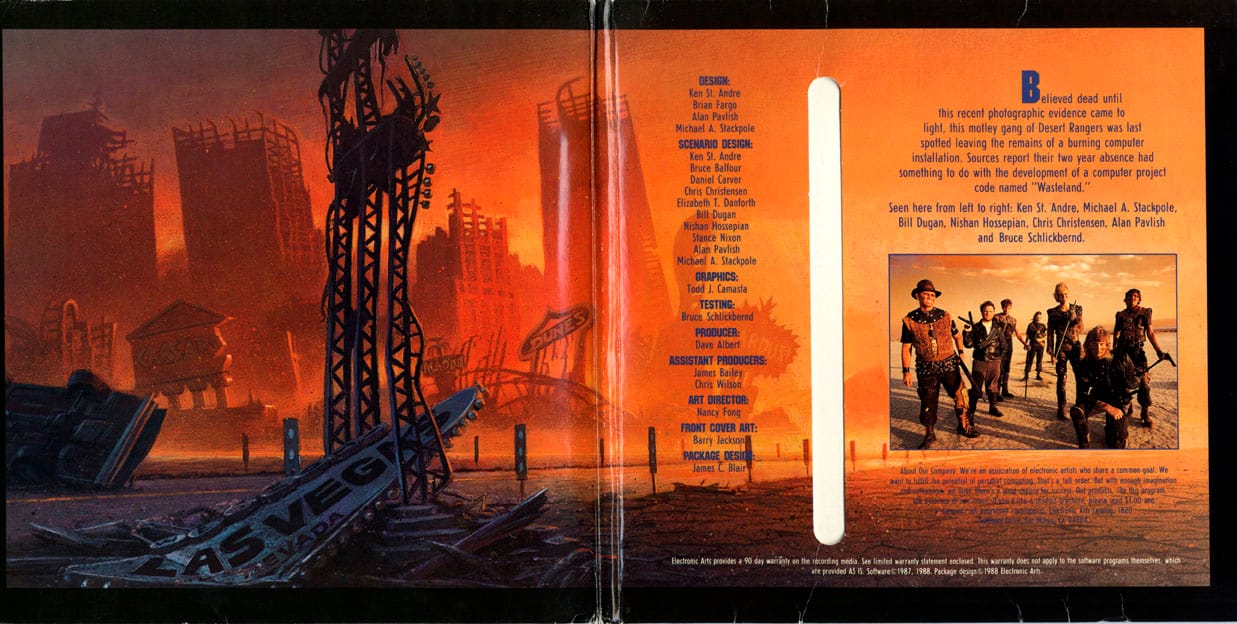

One aspect of EA’s marketing still resonates very strongly with me (thirty years on). EA would place full page ads in computer magazines and comics showcasing — wait for it — the designers and developers! In some cases, they would have slick looking portraits of the game designers or ‘software artists’ (such deliberate choice of term!) inside the box itself. Think about that for a second.

Oh sure, the games were mentioned. Small pictures of the game cover art were shown. But the centre of attention was undoubtedly the lead developers of the games themselves. This was incredible! Heck, some of the games even had the developer’s name in the title/art (Bill Budge and Pinball Construction Set come to mind).

EA — arguably the leader of the industry at that time — made a few decisions which need to be called out. First, they celebrated the individuals and recognized those people as key to the design, development, and promotion of a successful EA game. Kids like me were soon aware who designers like Anne Westfall were and paid attention to what she did. Not only did this give a personality to the game and the company, it inspired others to believe that, even alone, they could write software. That I could write software.

Second, they defined a language which altered perception of software as mystical, tended to by acolytes in a back room somewhere. They gave game developers titles which now may seem commonplace (‘designer’, ‘artist’) but, at the time, was groundbreaking. The idea that games were created in this confluence of science, magic, art, and business was pretty heady stuff. It really changed how I viewed computer software and my role in it. I could be both a consumer and a producer.

Finally, they seemingly empowered those designers to think and create outside of the box and to lead instead of follow. As with any new frontier, games at the time were not just variations on a theme; real innovation (and competition) was happening, both in terms of game design and development. This empowerment was even evident in the way EA paid their talent: like rock stars, using a royalty system. Heck, even EA game boxes looked like a record sleeve with their square aspect ratio, dramatic and expansive artwork, credit lists, and liner notes.

In fact, one might argue the entire engagement model EA used at the time was one designed to make their games and designers relatable on some (albeit elevated, fantastic) level. Like rock stars.

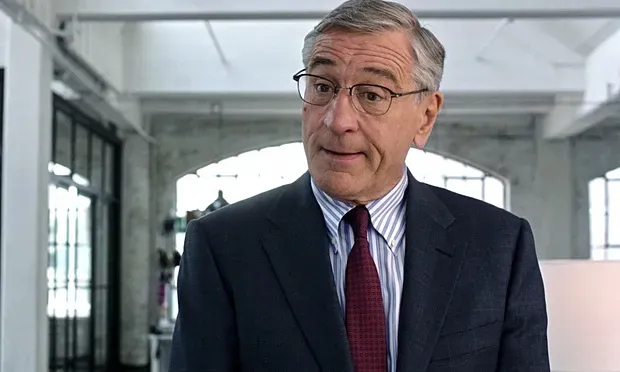

Rock stars

It turns out that those early years changed who I would become. While perhaps my first (practical, “I could do this for a living”) love was chemistry, computer science was my true love. Since then and for over twenty years I’ve worked on small projects and huge projects, with equally varied team sizes and skill sets. But the idea that a single developer or designer could alter the course and success of a project has stuck with me. Sometimes I’ve aspired to be that visionary…more often I’ve been able to learn from someone else in that role. Leading is one thing, but being larger than life, boldly putting your talent out there for all to see is another.

But is there a place for the archetypal rock star designer or developer in modern product development? Or, more facetiously, should we be celebrating those individual designers and developers with liner photos or product naming considerations?

The role of ego

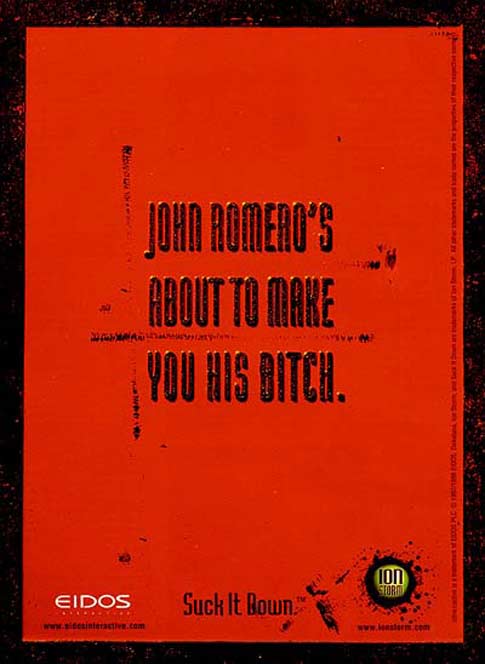

The use of the term ‘rock star’, above, was deliberate, if not also equally argumentative (I physically cringe when I see it used in job postings). Often the connotation of a rock star is that of inflated ego, with incredible demands, subject to whim, etc. But if they can back up that attitude on the stage with incredible performances, we often accept the baggage that comes with them — should we?

I’ve been lucky enough to have worked with several really smart computer scientists over my career and I’ve learned enough to know that brilliance is independent of an inflated ego and fickle behaviour. That said, there are certainly brilliant people, in all fields, whose presence (and their success?) might be diminished if their ego and bravado was more balanced (Steve Jobs is an obvious example, but also Peter Molyneux (of Populous fame), John Romero (of Doom, Quake, etc. fame), and outside of the product development fields, someone like Kanye).

The role of industry maturity

I think one dramatic difference between game development 30 years ago and product development now is their relative maturity as industries. There was a feeling of a gold rush on platforms like the Commodore 64 in the 80’s: the boundaries of the platform had yet to be fully mapped, the rules surrounding acceptable game design patterns were ad hoc and easily bent, and the industry was still testing itself.

The iOS app development surge of the past decade is perhaps a fairer contemporary comparison. The fact that someone could single handedly design, code, market, support — and profit from — a successful iPhone app ten years ago feels like the same sort of environment that allowed a team of one or two to create amazing Commodore 64 games. Perhaps there needs to be the right conditions for rock star designers and developers to exist, to be accepted, and to flourish. Perhaps modern, larger scale consumer or enterprise product development just doesn’t encourage visionaries who grab control of a product’s success through sheer will and technical virtuosity.

While there will always be new industries forming, ready for individuals and basement shops to lead the gold rush, the tech industry is so much larger now than 30 years ago. Where and how people find inspiration and their idols is as varied as the content and scope of the connected world.

The state of the union

I can’t argue with the end result of having such strong developers and designers to look up to during obviously formative years of my youth — I really loved those games and knew who had designed and developed them. So, does the early EA model of grooming their stable of designers as rock stars translate to modern product development?

No, I don’t think it does, as the result of several fundamental changes since the 80’s.

First, the world is so incredibly well connected. I no longer need to wait a month to get the next issue of Compute!’s Gazette in the mail so I can learn about the latest sprite blitting technique; hurrah! Most of us can easily find our own online communities and, as those tribes self organize, can help decide what constitutes a rock star or an exceptional talent. Open source projects rally behind a guiding developer as much as industries rally behind thought leaders.

This connectedness also changes how we, as potential product designers and developers, learn. The opportunities available to us, both in terms of inspiration and implicit and explicit learning, are wonderful. We no longer necessarily need to hear which one or two games (and designers) are the gold standard for that year, as decided by a single games company. We no longer need to learn techniques from a mail order book that is stale before it arrives. And while we can still read books (yes!) we have so many other options to learn, to develop our own sense of what constitutes an idol, and develop our sense of purpose and self within the larger community.

Second, software product development as a discipline has matured significantly in 30 years. Hardware, design and development tools, and even processes have progressed to a point where we (hopefully) can spend more effort on the product instead of wrestling with infrastructure. The democratization of software product development tools and processes is an ongoing effort, but one which has already meant that almost anyone can learn to write code, create programs, and share them with the world. By opening up this process to more people, we can find designers and developers to look up to in our neighbourhood as easily as from a giant games studio.

Third, in the same way design and development tools are accessible to most, the commoditization of engagement platforms and tools has had an immeasurable impact. Such availability means that not only can we establish and nurture our online communities, we can contribute to the conversation, the collective body of work, and affect the course of an industry (sometimes with a single tweet or posted portfolio piece). I suspect the empowerment evident in Twitter, Pinterest, Github, Behance, reddit and so on has had the same effect on today’s hungry youth as EA’s ads did on me decades ago.

Of course this level of engagement isn’t without cost. Many find it difficult to keep abreast of all the developments or conversations within an industry, let alone recall or search for specific information. But, oh my, what a challenge to face — too much information and too many ways to access it!

Fourth, the concerns and details of modern software and product development efforts have the potential to be so much bigger in scope and complexity than games of the 80’s. That isn’t to say that there aren’t small start ups and game shops making some really cool stuff, but marketing that cool stuff with EA-style ads is risky. Teams are bigger, projects take longer, and marketing is more focused on how the product is solving real user problems. Perhaps as it should be.

There will always be a need for leaders in any industry — they inspire, they innovate, they make us question the status quo and attack problems differently. What makes those individuals worthy of respect is up to the community and, perhaps more importantly, the personal belief systems of the individuals making up that community.

We need to acknowledge bold and calculated risk taking, and the willingness to share knowledge and accolades with others. We need to understand that software product development has changed, has become more complicated and nuanced, and that things are just…different.

Calling out individuals for given software projects with full page ads isn’t an inherently bad thing, I just don’t think it is necessary any more — the community will figure out who the rock stars are. We’ll applaud them. We’ll question them. We’ll learn from them. We’ll aspire to be like them. We’ll be motivated by them. And we’ll all be better for it.