How much can you learn in three days?

A three day weekend at a summer cottage flies by! But those three days visiting your in-laws — maybe not so much?!

So where along that spectrum does tackling a big juicy problem as part of a Google design sprint lie? In late February, I participated in a three day design sprint. I’ve had a few days to reflect on the experience; consider these my retrospective notes.

What went horribly, devastatingly wrong

Spoiler alert! Nothing went horribly wrong. There were things we could have done differently, but we were fortunate that careful preparation and solid facilitation kept us on track and able to work through the design sprint process.

What went right

I like that the design sprint process prescribes certain behaviors and encourages a certain environment. This makes sense to me. Keeping people focused on the task is helped by, for example, removing decisions like where to go for lunch. By default, trust the process!

The location has a role to play

Don’t underestimate the power of an inspiring (or, at least, not distracting) space. During preparation for the sprint, we looked for locations that:

- weren’t too far or too difficult to get to (relative to Kitchener-Waterloo);

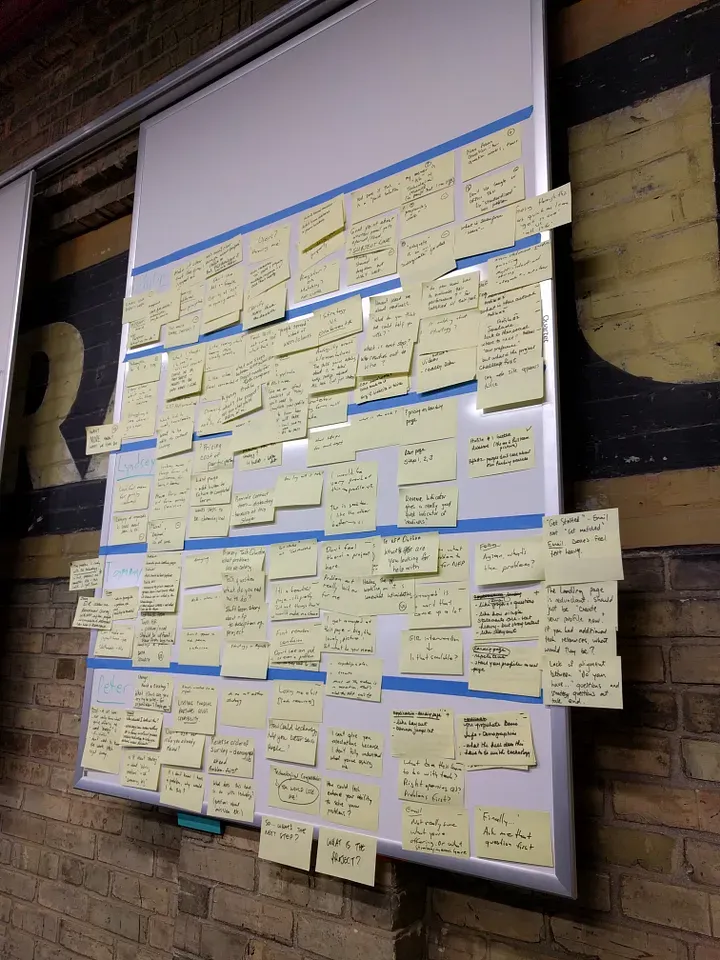

- had whiteboards and flat surfaces (suitable for covering with sketches, Post-Its, etc.);

- were bright and open;

- provided straightforward wireless internet access;

- ideally had a simple AV solution (e.g. flat panel or projector with HDMI connection).

We chose a great location in Elmira, about 20 minutes drive from Kitchener-Waterloo. This physical separation helped, I think. Not only did it prevent people from ‘popping out’ to run an errand (thus inviting time slippages), but the drive to and from the site provided an opportunity to mentally prepare or decompress. Don’t underestimate the energy you’ll expend during a design sprint — you’ll want to ‘come down’ at the end of the day and get enough sleep.

The owners of the space were very accommodating and, given they were potential users of the system we were designing (they’re a progressive environmental engineering firm), they actually participated in user testing of our prototype. This addition to the user testing roster was last minute, so don’t forget to keep your eyes open when looking for people to test your prototype!

Bring your A-Team

The sprint book recommends a team to be seven people or fewer. We went with five (excluding the facilitator). This worked out well for us: we all seemed to get a chance to talk during discussions and the cross section of experience from each member was what we needed.

So what about team member experience? How should what you know of people’s skills and work experience influence the team composition? In our case, while the sponsoring organization was very familiar with the problem space, exploring options for addressing that problem was in its infancy. We needed the team to be comprised of sector experts (social/not-for-profit, technology) without necessarily being experts in the proposed solution. We wanted open-minded, design-sympathetic folks first and foremost.

Feed the machine…properly

As some more progressive tech companies have discovered, if you feed people yummy, healthy food, they’ll keep working and make better decisions. Design sprint participants are no different! We had light breakfasts (fruit, smoothies, etc.), snacks for breaks, and balanced lunches (sandwiches, pasta, salads, etc.).

We didn’t need to worry/waste time thinking about where to get food or a drink. We didn’t need to make sure people got back in time. This system worked out really well.

Interesting — and interested!

During the initial (pre-sprint) exploration of the problem, we’d conducted interviews with potential users. We’d tried the solution on for size, performing elevator pitches to anyone who’d listen. We read more white papers than we want to admit. But, as this exploration phase progressed, we met some really interesting people! They understood what we were trying to do and were incredibly generous with their time and energy (it takes energy to be interviewed and add value to that conversation).

As a result of these initial interviews and the strong community roots of both the Decider and Facilitor, the quality of our user participants was excellent. The feedback we received was fair, detailed, and presented within the appropriate context. Participants represented their organizations honestly. They appreciated the scope of the work we were doing (“our prototype only addresses a small section of the larger solution…”). In short, they were very helpful.

A strong brief

One of the artifacts created in preparation for the design sprint is the design brief. This document collects details specific to the design sprint, including scheduling, team composition, problem statement and history, and how to think about going forward.

Don’t underestimate the role of this document (or its constituent pieces of information). Not only will the document be useful during the sprint, the process of its deliberate creation will force you to answer tough questions, craft your words with intent, and think about what you want to get out of the week.

What we could have done better

I know I shouldn’t love this part of a retrospective as much as I do, but I can’t help it — figuring out what went wrong unearths the potential upside of the process for the next time!

Big picture questions…

Part way through the sprint, our Facilitator called attention to the fact that several conversations were causing the team to run well over the time window for a specific task. We all agreed that while the topics of these conversations were absolutely relevant to the larger system discussion, they were not specifically related to the problem we’d decided we wanted to tackle for this design sprint. They were distracting us and threatening to derail our progress.

So, what caused this issue? The system we were working on had been discussed prior to the sprint by only a subset of the participants, although everyone had been given a summary of the problem and proposed solution at the outset of the sprint. Furthermore, while the problem and solution (a web app) had been discussed by some members, the solution hadn’t been explored at all from a business perspective — in retrospect, there was little agreed upon business context for the proposed solution.

If this team were to hold another design sprint, part of the preparation would need to include answering some fundamental questions in order to create (and document!) that context. I don’t think the design sprint process failed in any way in this respect, merely that our team’s collective understanding of the business context — specifically, how the web app would be paid for — wasn’t understood (yet).

Hi, I’m Matthew…

The team assembled (I use that term very deliberately) for this design sprint had one thing in common: a good relationship with the Decider. But the topology of the team was very much ‘hub and spoke’; all the team members knew the decider, but many didn’t know each other.

So, while the composition of the team relative to skill mix was discussed prior to committing to a design sprint, how well that team would work together was relatively unknown. The Decider was confident in her choice of team members and, ultimately, the team was fairly strong. But we could have crashed and burned (oh, Top Gun) using an untested and freshly assembled team, especially during the prototyping phase. So perhaps we got lucky.

Wayfinding

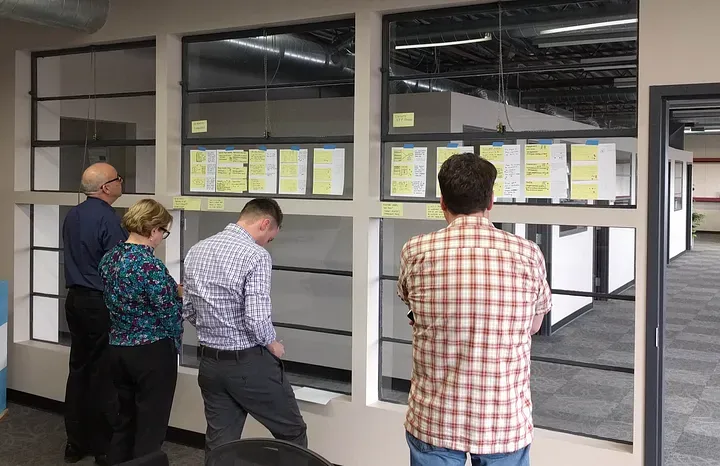

Our sprint location was pretty great: lots of natural light streaming through large windows, whiteboards and empty walls ripe for Post-Its, and a separate, quiet room suitable for testing our prototype with users.

However, getting from the parking lot across the street into the office we were using wasn’t obvious: through one of two doors, walking up to the third floor while winding through piano repair shops, vintage furniture, open spaces, and unmarked doors. We ended up having to watch for participants at certain points to ensure they didn’t get lost. It worked out in the end but, were we to use the location again, we’d provide participants with explicit directions.

Put yourself into the shoes of your participants and try to make their experience as clear and pleasant as possible.

Recruiting representative users

While planning the sprint, we hoped to get three representative users from each of the sectors involved. We didn’t have any problem recruiting users from local not-for-profit organizations. We did, however, find it a bit challenging to recruit participants from technology companies (often the companies indicated their HR employees didn’t have the time to spare, independent of their support for our project).

For any future design sprint, I think we’d need to reach out more widely to secure participants (especially tech company participants) and more clearly enumerate the benefits to participants.

Key observations

You need to ensure you have the right set of skills available on the team in order to create the most effective prototype possible. This is likely more important with a compressed, three day long design sprint than a week long design sprint. Self-awareness (what do we know we can deliver?) and diversity are strengths in this regard. The problem (and solution) we were tackling straddled several user types, several sectors/knowledge domains.

The quality of the feedback depends not only on careful test administration, but also on the quality of user participants. Sometimes the people you’re showing your prototype to will be quiet. Sometimes they won’t stop talking. Often they’ll identify a potential problem (great!) but won’t provide more detail, even when the administrator of the test tries to tease it out of them (rats!).

Without taking the collective plunge associated with participating in a design sprint, work on the project may have stalled. By getting the right people in the room, trusting the design sprint process, and putting in a solid, creative effort, we made demonstrable progress. We gelled as a team, learning our respective strengths. We also got to talk with some awesome people, and that was perhaps my favourite part.

Acknowledgements

Cathy Brothers, CEO of Capacity Canada, championed and sponsored the design sprint. Cathy was able to pull together a formidable team (thank you team!) on relatively short notice, handle logistics associated with the event, and contribute sector insights crucial to the design work during the sprint.

Mark Connolly of Zeitspace acted as sprint master for the design sprint. His guidance before and during the sprint were critical to its success. His enthusiasm for design is contagious while his experience allowed him to confidently adapt to any situations we found ourselves in. Mark was the perfect guide for our team.

Thank you to our representative users that helped with both preparatory research and prototype testing. We were lucky to have participants from both not-for-profits and tech companies. Their contributions were detailed, relevant, and motivating.